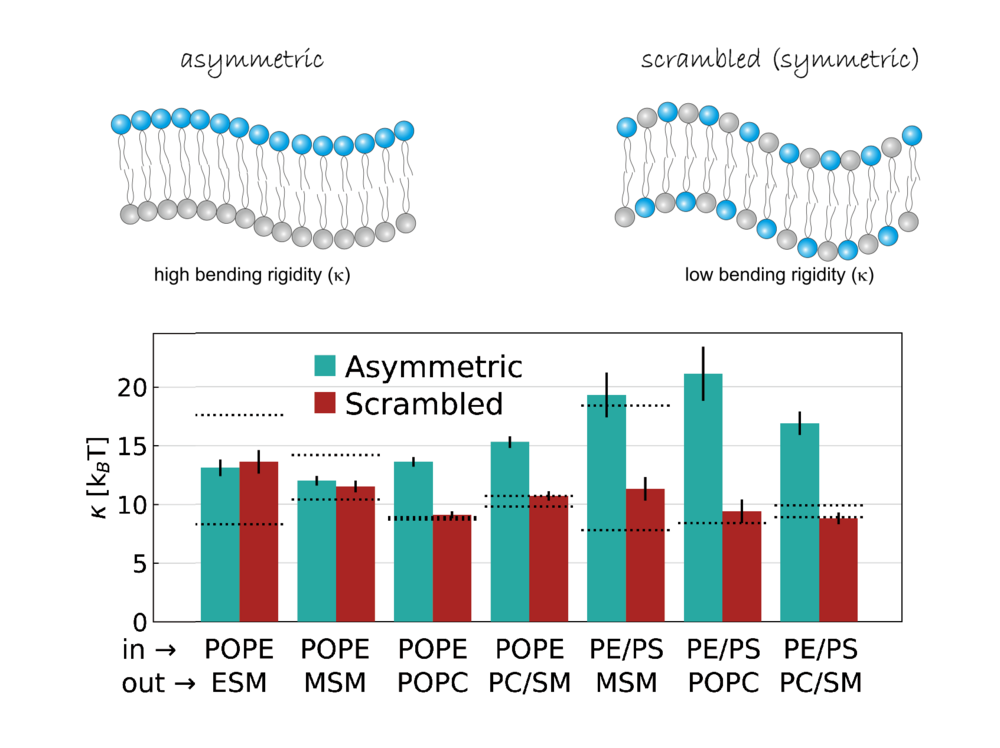

Asymmetric membranes are surprisingly rigid

Cells have an outer envelope, the plasma membrane. This membrane protects the cell, but it also has another important function: it contains many small proteins that react with their environment.

An exciting area of research is the uneven distribution of fat molecules (lipids) across the membrane. This distribution is known as membrane asymmetry. It is precisely controlled by certain proteins - flipases, flopases and scramblases.

We investigated how this membrane asymmetry affects the strength of the membrane. We used a special technique called neutron spin-echo spectroscopy. This allowed us to measure the flexibility of artificially produced membranes.

The result was surprising: asymmetric membranes were particularly rigid. They were even more rigid than symmetric membranes made from the same lipids.

Why this is the case is still being investigated. But our results show that the asymmetric distribution of lipids may make the cell more resistant. This may allow the cell to respond more quickly to stress and protect itself.

- Link to the article: M.P.K Frewein et al., Biophys. J. 122, 2445 (2023), DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2023.04.025.

Design: Georg Pabst, data from Frewein et al., Biophys J. (2023), License: (CC-BY 4.0 DEED)

From: Piller et al, RSC Appl. Interf (2025), License: (CC-BY 4.0 DEED)

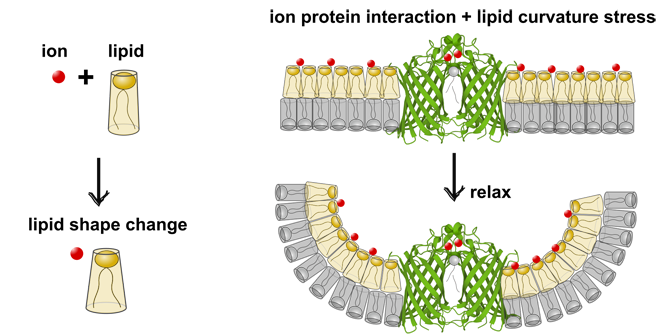

Metal ions influence enzyme activity by changing the membrane curvature stress

Metal ions are important helpers for proteins. They often ensure that proteins function properly and remain stable. In the case of the enzyme OmpLA (an enzyme in the outer cell membrane of Gram-negative bacteria), calcium ions help it to remain in its active form.

We investigated how OmpLA degrades (hydrolyzes) lipids in the membrane. We tested different membranes: electrically neutral and negatively charged, and with symmetrical or asymmetrical lipid distribution.

In membranes without charge, OmpLA was more active in symmetrical membranes than in asymmetrical membranes. This is because there are no curvature stress differences between the two membrane leaflets. Surprisingly, the opposite was true for charged membranes, where OmpLA was more active in asymmetric membranes.

Small-angle X-ray measurements showed that the shape of the charged lipids changes when calcium is added. This reduces the differential curvature stress in asymmetric membranes, which increases enzyme activity. A similar effect occurs with sodium ions. They affect the shape of the lipids but do not bind directly to the protein.

Our results show that metal ions do not only react directly with membrane proteins. They also affect their activity indirectly by changing the shape of the lipids.

- Link to the article: P. Piller et al., RSC App Interf 2: 69 – 73 (2025) DOI: 10.1039/D4LF00309H.

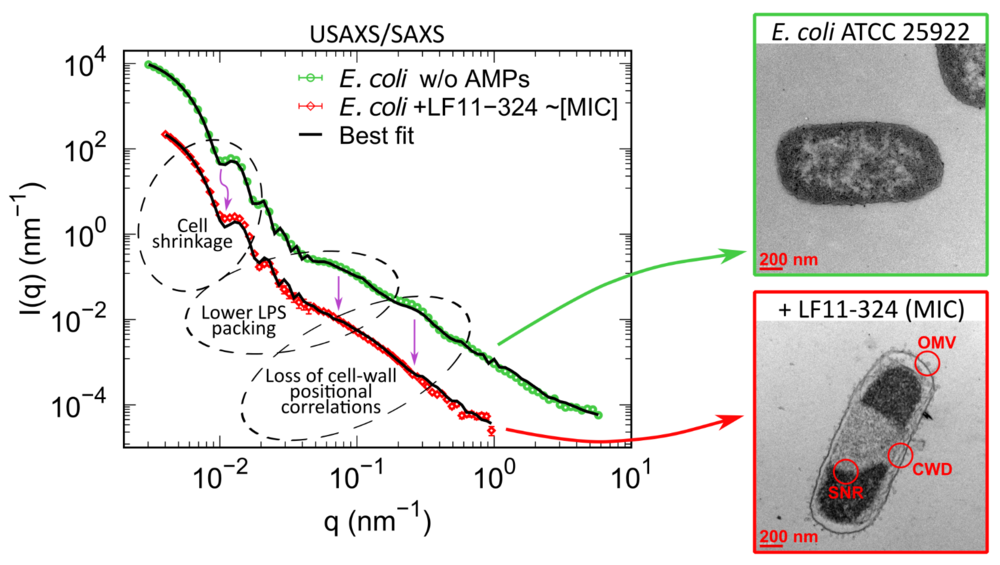

Time-resolved scattering on living cells: How antimicrobial peptides work

The development of new antibiotics is not progressing fast enough, while more and more bacteria are becoming resistant to existing drugs.

One promising alternative is antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). These are part of the natural immune system and work differently than conventional antibiotics. Instead of interacting with bacteria through a special lock-and-key mechanism, they attack multiple cell components more broadly, such as the protective lipid membrane. As a result, bacteria have less chance of developing resistance. But while AMPs are promising, researchers do not yet know exactly how they work at the molecular level inside cells.

To better understand how AMPs work, we studied live E. coli bacteria. We used two special analytical techniques:

- (Ultra)small-angle X-ray scattering ((U)SAXS)

- Neutron Small Angle Scattering (SANS) with contrast variation

These methods allowed us to follow in real time how quickly the AMPs acted on the bacteria. Our analyses showed that making pores in the membrane alone is not enough to kill bacteria. The most effective AMP in our study was particularly efficient because it reached the inside of the cell in large quantities the fastest and thus stopped bacterial growth.

- Link to the article: E.F. Semeraro et al., eLife 11, e72850 (2022), DOI: 10.1101/2021.09.24.461681.

Aus: Semeraro et al., eLife (2022), Lizenz: (CC-BY 4.0 DEED)

Overview of important contributions

- P. Piller, P. Reiterer, E.F. Semeraro, & G. Pabst, Metal ion cofactors modulate integral enzyme activity by varying differential membrane curvature stress, RSC App Interf 2: 69 – 73 (2025) DOI: 10.1039/D4LF00309H.

- M.P.K Frewein, P. Piller, E.F. Semeraro, O. Czakkel, Y. Gerelli, L. Porcar & G. Pabst, Distributing aminophospholipids asymmetrically across leaflets causes anomalous membrane stiffening, Biophys. J. 122, 2445 (2023), DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2023.04.025.

- P. Piller, E.F. Semeraro, G. N. Rechberger, S. Keller & G. Pabst, Allosteric modulation of integral protein activity by differential stress in asymmetric membranes, PNAS Nexus 2, 1 (2023), DOI: 10.1103/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad126.

- J. Jennings, & G. Pabst, Multiple routes to bicontinuous cubic liquid crystal phases discovered by high-throughput self-assembly screening of multi-tail lipidoids, Small 2206747 (2023), DOI: 10.1002/smll.202206747.

- E.F. Semeraro, L. Marx, J. Mandl, I. Letofsky-Papst, C. Mayrhofer, M.P.K. Frewein, H.L. Scott, S. Prévost, H. Bergler, K. Lohner & G. Pabst, Lactoferricins impair the cytosolic membrane of Escherichia coli within a few seconds and accumulate inside the cell, eLife 11, e72850 (2022), DOI: 10.1101/2021.09.24.461681.

- M.P.K. Frewein, P. Piller, E.F. Semeraro, K.C. Batchu, F.A. Heberle, H.L. Scott, Y. Gerelli, L. Porcar, and G. Pabst, Interdigitation-induced order and disorder in asymmetric membranes, J Membrane Biol. (2022), DOI: 10.1007/s00232-022-00234-0.

- M. Kaltenegger, J. Kremser, M.P. Frewein, P. Ziherl, D.J. Bonthuis & G. Pabst, Intrinsic lipid curvatures of mammalian plasma membrane outer leaflet lipids and ceramides, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1836, 183709 (2021), DOI: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2021.183709.

- B. Eicher, D. Marquardt, F.A. Heberle, I. Letofsky-Pabst, G.N. Rechberger, M.-S. Appavou, J. Katsaras & G. Pabst, Intrinsic curvature-mediated transbilayer coupling in asymmetric lipid vesicles, Biophys. J. 114, 146 (2018), DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.11.009.

- B.-S. Lu, S.P. Gupta, M. Belička, R. Podgornik & G. Pabst, Modulation of elasticity and interactions in charged lipid multibilayers: monovalent salt solutions, Langmuir 32, 1355 (2016), DOI: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b03614.

- B. Kollmitzer, P. Heftberger, R. Podgornik, J.F. Nagle & G. Pabst, Bending rigidities and interdomain forces in membranes with coexisting lipid domains Biophys. J. 108, 2833 (2015), DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.05.003.

- E.F. Semeraro, M.P.K. Frewein, & G. Pabst, Chapter Fourteen - Structure of symmetric and asymmetric lipid membranes from joint SAXS/SANS, in Methods in Enzymol, T. Baumgart, M. Deserno (edts), Academic Press, 700: 349 - 383 (2024) DOI: 10.1016/bs.mie.2024.02.017.

- G. Pabst, & S. Keller, Exploring membrane asymmetry and its effects on membrane proteins, Trends Biochem Sci, 49: 333 -345 (2024) DOI: 10.1016/j.tibs.2024.01.007

- G.J. Schütz & G. Pabst, The asymmetric plasma membrane—A composite material combining different functionalities? BioEssays 45: 2300116 (2023) DOI: 10.1002/bies.202300116

- E.F. Semeraro, L. Marx, M.P.K. Frewein, and G. Pabst. Increasing complexity in small-angle X-ray and neutron scattering experiments: from biological membrane mimics to live cells, Soft Matter 17: 222 - 232 (2021) DOI: 10.1039/C9SM02352F

- D. Marquardt, F.A. Heberle, J.D. Nickels, G. Pabst, & J. Katsaras. On scattered waves and lipid domains: detecting membrane rafts with X-rays and neutrons. Soft Matter 11: 9055 - 9072 (2015). DOI: 10.1039/C5SM01807B

- D. Marquardt, B. Geier, and G. Pabst, Asymmetric lipid membranes: towards more realistic model systems. Membranes 5: 180 - 196 (2015). DOI: 10.3390/membranes5020180

G. Pabst, N. Kučerka, M.-P. Nieh, & J Katsaras (Hg), Liposomes, Lipid Bilayers and Model Membranes From Basic Research to Application, CRC Press (2014) ISBN: 9781138198753